A Volunteer’s Journey in Zanzibar: Interview with Zara Zlatanova

At R.O.S.A., our work is built not only on educational programs and digital empowerment but also on the human stories that emerge along the way. Each volunteer who joins our initiatives brings a unique perspective, shaped by curiosity, courage and a desire to contribute to meaningful change. For us, these individual journeys are a vital part of the impact we create together.

As part of our ReCoding Africa mission in Zanzibar, we sat down with one of our volunteers, Zara, to reflect on her experience on the ground. Through her insights, we gain a deeper understanding of what it means to learn, teach, adapt and connect across cultures. Her story captures the essence of volunteering: personal growth, genuine human connection and the transformative power of education when shared with intention and empathy.

Below, we share the full conversation.

We hope her reflections will inspire future volunteers and highlight the importance of building bridges between communities, one experience at a time.

Below you can read our full interview with Zara and discover her journey in her own words.

When did your interest in volunteering begin?

My dream of volunteering in Africa started when I was 16. For a long time, it felt like a distant idea for someone my age. I didn’t believe I would be taken seriously—I was young, and my experience was just beginning to build. I had the desire but lacked the confidence that anyone would believe in me enough to give me that opportunity. But I was too ambitious to stop there. That’s how I discovered the Interact Club Vidin—not just a club, but an environment that gave me my first stable foundations. There, I learned how to work for causes, organize initiatives, and that good ideas have value when backed by persistence and teamwork. At the same time, my years at the “Yordan Radichkov” Language High School developed another side of me—proactivity. I wanted to join the Student Council even before I was sure what major I would choose at New Bulgarian University. I was active not only in volunteering but also in competitions, creative and scientific contests, and various initiatives that showed me that a person’s path isn’t defined by a single label. I enjoyed trying new things and challenging myself.

How did your African adventure begin?

My African adventure didn’t start by chance. For two years, I applied to volunteer programs focused on educating children in Africa, and I was approved several times. The reason I didn’t go was more about a lack of readiness, time, stable finances, and confidence that I could be useful and truly handle the challenge. But as I like to say, everything happens for a reason.

During a trip to Italy, I met someone with whom I later built a friendship. I shared my desire to work for people and communities with limited access to resources and opportunities. It was he who directed me to the non-governmental organization R.O.S.A.

I started an online marketing internship there, working on their digital communication—from social media content to ideas for visual and text campaigns. Without planning it, I became part of an incredible team with whom I continue to work tirelessly to this day. After weeks of intense work on their digital platforms, my efforts grew from posting on social media to a real chance to experience everything I had only read about or seen in clips. I received an offer to be part of their next mission in Zanzibar. I’m not sure I can describe in words the initial shock, because when I started the internship, I didn’t even suspect I would fulfill one of my biggest dreams.

This experience taught me to be more patient with my own decisions — not to rush into big steps when I don’t feel ready and not to underestimate the process before the result. The right time will come as long as you work in that direction. It also strengthened my belief that everything happens for a reason. There was nothing accidental about ending up in the right place, with the right people, at the exact time, because this “chance” meeting opened the path for me not only to another continent but also to my growth as a person.

What is R.O.S.A.?

R.O.S.A. (Remove Obstacles to Social Awareness) is a non-governmental organization founded in Rome, Italy, in 2014, with a mission to remove social and economic barriers to education. Its focus is not on one-time aid but on sustainable empowerment, through knowledge and skills that give people the chance to change their own environment.

The organization works with a global network of volunteers and creates programs that combine education, social awareness, and digital literacy. Some of its initiatives include training in languages, IT skills, coding, working with media, and artistic formats, making education more accessible and understandable. R.O.S.A. accepts both young people and students, as well as professionals from various fields for internships and volunteering, with tasks ranging from fieldwork to remote work.

One of its most recognizable programs is ReCoding Africa, an initiative focused on digital skills for youth, combined with cultural exchange and social integration. But beyond the specific modules and tasks, the organization actually teaches not just subjects but a new way of thinking, that education should be an equal opportunity, not a privilege. This is what makes it a platform that connects people, communities, and future opportunities without setting boundaries based on origin, profession, or age.

What was the goal of the program?

R.O.S.A. develops international volunteer projects through several core programs: ReCoding Africa, ReCoding Thailand, and ReCoding Vietnam. The choice of program depends on the country or region where the mission takes place, which is why the names have a geographical focus. In my case, my participation was in the ReCoding Africa program because the mission took place in Zanzibar.

Within ReCoding Africa, the main educational focus we worked on was the Teachers Training for Tomorrow (TTT) program—a module that prepares local future teachers through the Train-The-Trainer principle, where education is passed forward through new trainers from the community itself.

The goal of TTT was sustainable and measurable:

– To train local teachers and young people not just what to teach, but how to teach.

– To give them methods for structuring lessons, approaches to different audiences, and the confidence to continue on their own. We showed them how to work with platforms already widespread in Europe—Canva, Kahoot, AI tools, IBM Skills Build.

– To turn knowledge into a system that remains after we leave, rather than ending with our departure.

TTT doesn’t create one teacher; it creates many. Instead of being the final source, we were the initial one—the people providing the tools, and the local teachers—those multiplying the effect. This participation showed me that the true goal of volunteering isn’t to be needed forever, but to be useful once—strongly enough for it to continue afterward.

What was your role in the training?

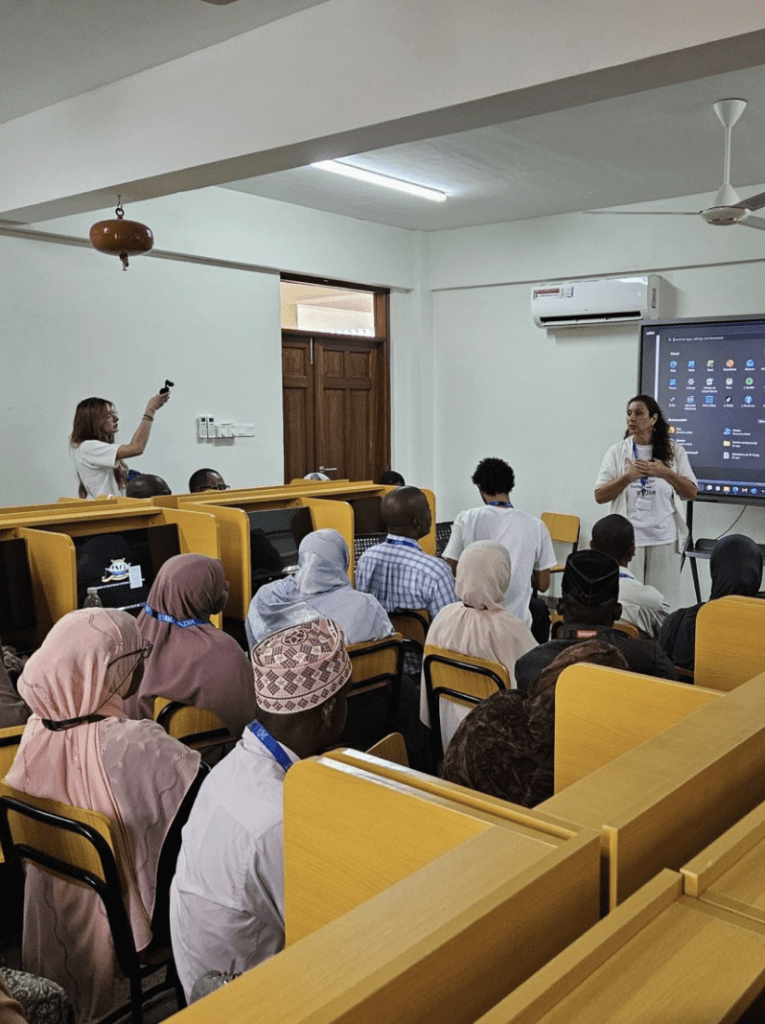

In the training, my role was as a video content creator. I was responsible for documenting the entire learning process, which meant filming all lectures and practical sessions. After the training module ended, my task was to edit the recordings and structure them as learning materials to be sent to the local teachers. The goal of these videos is to serve as future training resources, materials they can use independently, share with colleagues, and expand the effect of what was learned, without it remaining confined to the specific mission.

Additionally, I created content for R.O.S.A.’s social media. My work there included capturing footage from the field or during our free time, as well as editing short videos to present the organization’s initiatives in a reliable and understandable way to a broader audience.

What is the level of education there?

Based on my personal impressions, the level of education in Zanzibar is in the process of active development. At the beginning, the teachers experienced difficulties not because they lacked desire, but because many of the tools we used were completely new to them. However, they adapted extremely quickly. The most impressive thing was their persistence and curiosity. Instead of limiting themselves to the program, they took the initiative to learn more — asking additional questions, requesting new demonstrations, and insisting we show them features not initially planned.

They also excelled in team tasks. They were divided into groups and had to prepare a presentation in Canva, then present it. Honestly, the level at which they performed was impressive, especially considering how little time they had to master a completely new tool.

Moreover, the environment in the school itself was very different from the general perception of schools in Africa. They already had interactive boards, computers, and an environment that allowed for calm and effective work.

In schools for younger children, however, conditions varied. Some were more modest, others better equipped, but the biggest difference was in the approach to education. In some schools, the model is more traditional—children sit in the classroom, listen to the teacher, and follow the standard learning process. In others, the approach is much freer—more play, movement, and interaction between children is allowed. Personally, I found this valuable because it shows that education can be different, and childhood isn’t just about learning and discipline. Sometimes, the most important thing is for children to play, socialize, and experience, because that is also part of their development, no less significant than intellectual or physical abilities.

What approaches do the teachers use?

If I’m completely honest, my impressions of the specific methods teachers use daily are limited because our main work was related to training them in digital tools. However, I understood a few important things. Some teachers already use YouTube videos to support lessons or explain difficult topics in a more accessible way. But overall, digital tools are not a widespread part of their practice. Especially when it comes to AI-based applications, they hardly use them, mostly due to a lack of training, not a lack of desire. And that’s precisely why our role there was so important. We showed them how various AI tools can ease their work, from creating learning materials to generating examples, visualizations, and interactive exercises. The goal was to give them tools that make lesson preparation faster and more effective.

What knowledge and skills did you impart?

During the training, we imparted a wide range of knowledge and practical skills to the teachers, which are extremely important for their work in the 21st century. Our main focus was to introduce them to digital tools, AI technologies, and communication methods that can significantly facilitate their preparation and increase student engagement. First, we worked on developing basic ICT skills, from basic computer literacy to working with online platforms. We taught them how to use IBM SkillsBuild and provided access to the High School Teacher Toolkit, which gives them ready-made learning materials, exercises, and resources.

The training also included developing skills important for the teaching profession: teamwork, constructive communication, confidence in presenting, giving and receiving feedback. At various stages, they had to work in groups, solve real problems, and present completed projects, something that significantly improved their collaboration and critical thinking skills.

Among the specific digital skills we imparted were:

– Working with Google Workspace—Google Slides, Google Forms, Google Classroom, etc. They learned to create interactive presentations, surveys, and various assessment methods.

– Interactive tools for engaging students, such as Kahoot. We showed them how they can turn the classroom into an active, dynamic, and more interesting space.

– Internet navigation, digital communication, and online security—topics directly related to how teachers use technology in the modern school environment.

– Project-based learning and video storytelling—teachers developed solutions to real problems like climate change, education, ocean pollution, and social challenges, using the learned tools to create presentations and short videos.

– Working with Canva for Education—they learned to create visual materials, presentations, and graphics, and I personally assisted with the video content part, guiding them on approaches to video storytelling.

A large part of the training was also devoted to the ethical and responsible use of AI—ChatGPT, Canva AI, and other applications. This was a completely new area for them, but their immense motivation and curiosity made the process extremely successful. Our goal was to give them tools to create learning materials more easily, prepare more structured lessons, and make their classes more interesting. In the end, each of them developed a project that included a presentation, data analysis, and a video element, proving in practice how they can master the many skills they learned in just a few days.

How would you describe the children there? What are they like in character and attitude?

Based on my impressions, the children there are… exactly what children should be — energetic, curious, smiling — but there’s something in their smiles that is different, something purer, more genuine, and inexplicably special. It was clear that they carried joy within themselves, not in the things they possessed.

What surprised me most was that I hardly saw any shy children. The moment they saw us, no matter which school we visited, they were the first to run toward us, hug us, hold our hands, and take pictures with us. The younger ones, who were even more energetic, climbed on us, wanted to play, constantly joked around, and sought attention. Their openness and ability to show affection without barriers was something that deeply touched me. There was no distance, no worry, just pure childlike trust. Their openness truly moved me.

But one moment I will always remember, at one of the schools, the teacher asked the children to sing a song especially for me. It was a completely unexpected gesture, and the way they did it, with shining eyes and huge smiles, moved me deeply. And when we brought them gifts, their reactions were another lesson. Whether the gift was big or very modest, their joy was sincere and immense. You could see how strongly they valued the gesture, not the value of the item itself. Their smiles at that moment were the most beautiful “thank you” a person could receive.

What are the learning conditions like, and how do they affect their development?

Based on my impressions, learning conditions in Zanzibar vary significantly both between different schools and between educational levels. There are places, like some colleges and larger schools, that have a more modern base—interactive boards, computers, spacious classrooms, and a more structured working environment. In such institutions, there are prerequisites for more modern learning and greater development opportunities. However, in many other schools, conditions are more modest. Often, classrooms are worn out, materials and equipment are lacking, and teachers rely primarily on traditional methods. Sometimes it was mentioned to me that in some schools, older disciplinary approaches are still used—I personally didn’t witness this.

Such practices can influence the emotional environment in the classroom and children’s attitudes toward learning. In one of the schools we visited, the children even had difficulty concentrating during the lesson—they were noisy, just talked among themselves, or paid more attention to us—not because of a lack of desire, but because the environment and classroom dynamics sometimes made concentration more difficult. This was an example of how material conditions and the organization of the learning process affect attention and discipline.

Despite this difference in focus levels, I was struck by how deeply ingrained the principle of school culture and discipline is. Whether the school is public or private, without exception, every child wore a uniform. This speaks to respect for the institution, a sense of belonging, and a striving to maintain order, even when conditions are more limited. The uniform is part of their identity as students and carries a certain seriousness toward education.

These differences affect not only children but also older students and youth. Many young people finish school but don’t continue to higher education, and others even drop out before finishing. The reason isn’t a lack of potential but rather the economic reality and environment in which they live. In the area we were in, life resembled a calm Bulgarian village, and I mean that in the most positive sense.

People were down-to-earth, welcoming, and calm. Their main activities were related to local trade, fruits, vegetables, handmade products, small family businesses that provided their daily income. In such an environment, many young people naturally start working early and orient themselves toward fields like tourism, sales, services, or handicrafts. Education isn’t always a priority, especially when the family relies on their help.

However, this doesn’t mean a lack of desire for development. On the contrary, in our work with the teachers, I saw immense motivation to raise the level of teaching, introduce technology, and make learning more interesting and accessible. And this inevitably affects the children. A good teacher, even in modest conditions, can be the biggest catalyst for change.

Overall, learning conditions have an influence but aren’t the only determining factor. Children show curiosity and a desire to learn, and teachers show readiness to develop. Initiatives like ours help bridge the gap between limited resources and the great potential we saw in every school we visited.

Nature, people, food, or culture— which did you like most in Zanzibar and why?

I can’t point to one single thing I liked most in Zanzibar because every part of the place touches you in a different way. Nature surprises you, people warm you, food astonishes you, and culture makes you look at the world through a new prism. Zanzibar isn’t one experience — it’s a whole series of moments that imprint themselves for different reasons.

The nature of Zanzibar is the first thing that made me stop and look around. The Indian Ocean is different from any sea I’ve ever seen — warmer, cleaner, and quieter (aside from large tourist crowds), and the sunsets are simply indescribable. In the area we were in, there were no highways or huge roads. Everything was much more modest, and on both sides of the road, you only saw greenery, palm trees, and small houses. In many places, nature seemed to be reclaiming its territory.

And after all that came the most unexpected experience: swimming with dolphins. I was convinced we’d see them in some enclosed area, but instead, our boat took us into the middle of the ocean, where we simply had to jump in. A family of 7–8 dolphins swam around us, so close that I could feel their movements in the water. They played, spun, approached us, and then disappeared with incredible speed. We got back on the boat, chased them, jumped again, and this repeated several times. They weren’t bothered by us at all — quite the opposite — we mutually enjoyed each other.

People in Zanzibar live more modestly than us, but that gives them a special sense of happiness because they know how to enjoy the moment and appreciate the small things. From the first days, I felt incredibly accepted. While walking the streets, strangers constantly approached me, asked how I was, and wondered where I was from. If I looked confused or glanced around, there was always someone offering help without expecting anything in return. Their warmth isn’t “part of the service”—it’s part of their character. And that’s what makes them so memorable. In Zanzibar, people aren’t just part of the landscape—they themselves are one of the biggest reasons the place feels so different and so alive.

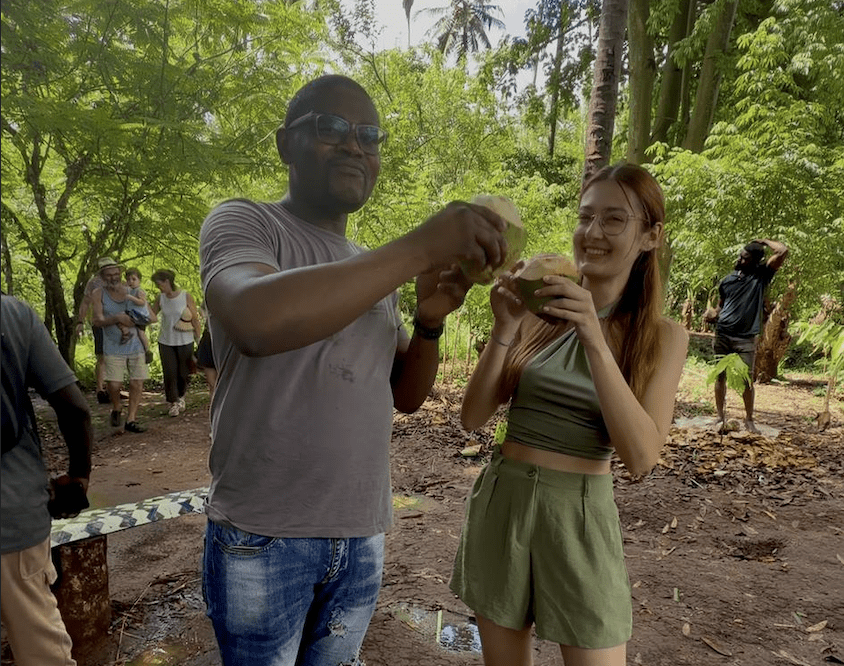

The food in Zanzibar surprised me not by being “exotic” but by being much more natural than what we’re used to. Everything is fresh, from seafood literally just caught to fruits. Even the simplest dishes felt different simply because the products are local and not processed the way they are back home. I ate things I normally wouldn’t choose, but there they just fit the atmosphere: fish prepared simply but with incredible flavor and typical sauces and spices, chicken curry or other chicken dishes prepared in non-standard ways for us, chapati, and of course, rice, which is part of almost every meal. However, the fruits left the strongest impression — mango, pineapple, coconut, sugarcane (which became my absolute favorite) — everything was so aromatic that I felt like I was tasting them for the first time in my life. I drank coconut water straight from the coconut, and the difference from what we buy in Europe is huge.

The culture in Zanzibar is one of the most palpable differences I felt. Most people there are Muslim and quite religious, which was new to me at first because I didn’t know this religion had so many clearly expressed rules and restrictions. For example, a man and woman who aren’t family can’t greet each other—something I didn’t know and in the first days put me in a slightly uncomfortable situation. Over time, however, I began to understand the logic behind these norms and to respect them. They also have fixed prayer times, four times a day, which meant our schedule had to end on time so as not to disrupt their routine. This was part of daily life there, and instead of hindering, it helped us see the rhythm of their life from within. Despite all cultural differences, they were extremely tolerant toward us. They respected the fact that we were from another culture, and no one—neither in the schools nor outside—judged us for the way we dressed, even though our clothes were much more revealing than theirs. Of course, we also adapted and tried to be respectful of local norms. The cultural difference was felt—that’s inevitable when two different worlds meet. But definitely not in a negative aspect. On the contrary: it showed us a new way of life based on respect, order, and calm, and that made our experience even more valuable.

What did you learn about yourself from this adventure?

This adventure showed me much more than I expected, and the main thing I learned was about myself. First, I realized that I adapt much faster than I thought. In a different culture, different conditions, and a different rhythm of life, I felt surprisingly confident and calm. I also learned something very practical: that I can work effectively even in extreme situations. I was editing videos in the car, on bumpy roads, while everything was shaking and our time was limited. And despite that, I succeeded. This showed me that when necessary, I can organize myself, be fast, and deliver results even in conditions that are far from ideal — including frequent power outages or lack of internet.

I also discovered how important it is to be more patient with myself. The truth is, the strongest criticism came from me. I noticed mistakes that only I actually saw, while people around me accepted them far more calmly. This made me think. I realized that sometimes I’m too hard on myself and that this doesn’t help me — it only prevents me from seeing the bigger picture. Gradually, I began to realize that there’s room for mistakes, for repetition, for learning, and that not everything needs to be perfect to be valuable. Zanzibar taught me to give myself a little more freedom and not punish myself for things no one else would consider a problem.

Moreover, I discovered that I work much better in a team than I imagined. There, I was surrounded by people with different personalities, different ideas, and different working styles, and yet we managed to understand each other, help each other, and create results that wouldn’t have looked the same if I had done them alone. This showed me that teamwork doesn’t distract me—it develops me. I also realized something else: that communicating with people gives me energy. The acquaintances, conversations, shared moments… These didn’t tire me—they charged me. I saw that when I’m in an environment where I need to communicate, explain, support, or simply listen, I actually become the best version of myself. And finally—Zanzibar confirmed something I’ve always felt: that I’m an adventurer at heart. Not because I “discovered” it there, but because the very fact that I spontaneously packed my bags and traveled halfway around the world proves it. This experience didn’t change me as much as I thought—it simply showed me who I’ve been all along.

Would you spend your retirement years in a place like this?

I think I would spend part of my retirement years in such a place, not because I want to escape something, but because Zanzibar offers exactly the kind of atmosphere a person begins to appreciate more with age: warmth, humanity, closeness to nature, and a cleaner rhythm of life. At the same time, I’m someone who loves dynamism, movement, change, and constant new experiences. That’s part of my character, and I couldn’t completely leave it behind. So I can’t imagine living there full-time for my entire life. But I can imagine something else, very clearly: Zanzibar being a place I return to again and again, a place where I spend long periods, seasons, months. A place that transforms from a “destination” into a “second home.”

My first visit was just the beginning, and I know the next ones won’t be the same — they’ll be even longer, even more meaningful, and even more connected to me.

I’m also grateful that this experience made me appreciate even more the things I already have at home. We often take for granted the conveniences and opportunities we have in Bulgaria and accept them as a given. There, I understood that many of the things that are “normal” for us are actually privileges. And this perspective brought me a new kind of respect for my own environment, home, and daily life. I’m grateful for the team I was with—for their patience, support, and for making my stay easier, more organized, and more meaningful. There were moments when the work was intense, conditions were unstable, and time was limited. And yet, not for a moment did I feel alone in my tasks. That’s something I’m sincerely grateful for. I’m also grateful for the small things: the conversations with local people, the children who greeted us with smiles, the unexpected moments—even the taxi driver who endured my 50-minute emotional crisis on the way to the airport back to Bulgaria. All of this made me see life more broadly and appreciate both the big and small details more.

Why should people follow your example?

I don’t think a person needs to go to the other side of the world to “prove” something, but I believe that when you step out of your own environment and go somewhere where life looks different, something important happens: you start to see the world more clearly, understand people more deeply, and, most importantly, understand yourself. The reason to follow such an example isn’t to be a hero. The reason is that volunteering changes you permanently. It makes you develop patience, adaptability, respect for other cultures, and greater gratitude for your own reality. You learn to work in a team, communicate confidently, and handle unpredictable situations. These are skills not learned from textbooks but from experiences.

There’s something else: when you see how much a gesture, help, training, or simply a presence can mean to someone, you understand that even small actions matter and that change doesn’t come from grand speeches but from real work on the ground. And if someone feels within themselves a desire to take such a step, to help, get involved, experience something different, and be part of a meaningful cause, they can volunteer with the organization R.O.S.A. The opportunity is open to anyone who wants to contribute and see the world from a more genuine perspective.

A three part series made by Zara during her volunteer journey in Zanzibar

🌍 Join Our Mission

R.O.S.A. continues to deliver free ICT education across Africa, Thailand and Vietnam through the Cisco Networking Academy and the IBM SkillsBuild Platform. With the support of partners such as the Cisco Foundation, IBM and international institutions, we work to build a more connected, equitable and digitally empowered world.

👉 Learn more: www.rosaservices.org

📧 info@rosaservices.org